For most Christians, the translation process is mysterious. We know that it happens, and that many people are very opinionated about the various versions. So what goes into the translation of a text? Let’s start with these two foundational realities.

1) All translation is interpretation.

2) One translation can not be fit for every purposes.

If there is interest, I can expand on one or both of those points in the future. Instead, I encourage you to keep those thoughts in mind while we continue. For simplicity, I’ll break the process into steps, but they mush & smush not so cleanly in practice.

Role of the Finished Texts

Before you start, one needs to establish how the texts will be used. The six general journalist questions are helpful here – Who? What? When? Where? Why? How? These are quick answers for the Psalms in the Urban Monastic Breviary Translation.

Who (will use it): An ecumenical group of people. They have different life stages, reading levels, academic achievements, ages, and religious backgrounds.

What (is the result): To publish 150 Psalms (plus Canticles) into English & French for a monastic breviary online, in apps, in audio, and in print.

When (will it be used): The psalms are a part of each fixed hour prayer, every day of the year.

Where (will they be used): The psalms will be used for both private and corporate prayer in homes, and churches.

Why (will they be used): Our mixed & ecumenical group deserves beautiful psalms to pray together. Texts that are informed by our traditions, but not of one specific denomination.

How (will they be used): The psalms will be prayed (read silently, aloud, chanted, or sung) individually or together.

There is a page on about these Translations that shares our general guidelines.

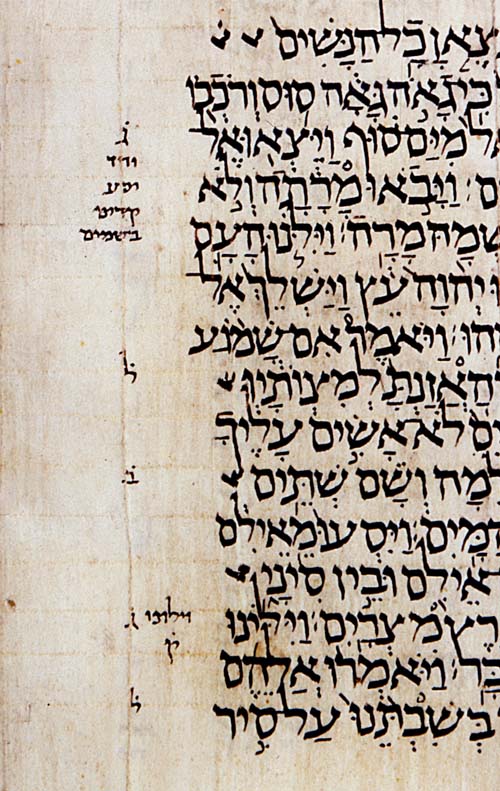

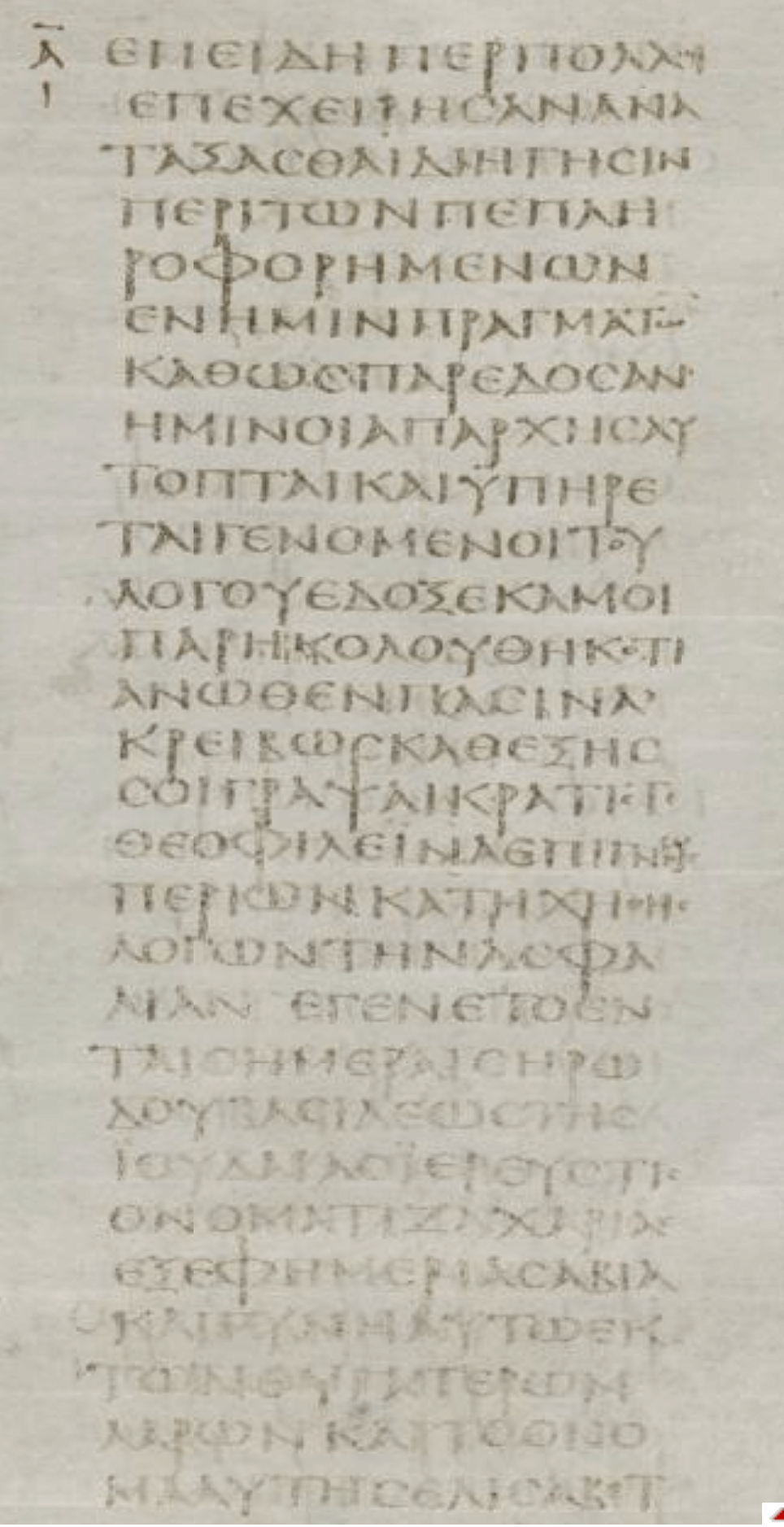

Selection of Sources

This is far more complex than it might sound. It is difficult working from small fragments of parchments, establishing the various textual lineages, and discerning the textual changes. This is how we get to our modern Hebrew and Greek texts of various biblical sources. These compiled sources are also under various copyright protection and licensing schemes.

For this project, we have settled on the following five sources

- Latin: Thesaurus Liturgiae Horarum Monasticæ (1977)

- Latin: Liturgia Horarum (2000)

- Using the Nova Vulgata (1979/86 – original text translation)

- Gregorian Chant/Music by l’Abbaye Saint-Pierre de Solesmes

- Hebrew: Westminster Leningrad Codex (~1008)

- Greek: Septuagint (LXX)

- Greek: Codex Sinaiticus (325)

- Greek: SBL Greek New Testament (SBLGNT)

Initial Translation

Working line by line through a passage, we get a first draft of a given passage or text. There is the grammatical work to understand the sources, and I make a rough attempt to synthesize the texts together. This helps me to hold them each in mind as I wrestle through phrasing into English & French.

With the rich monastic history of using these texts in Latin, we’ve made the decision to allow the grammatical structure of the Latin to inform most of our structure. This includes how the lines break and the placement of our midpoints (*) & daggers († – these indicate that the mid-point is on the next line instead of the end of the first line you would expect). The Latin was recently updated to use original source texts (in the 1970s) over the work of St Jerome of Stridon. Jerome translated the Bible into Latin from the Greek sources of 4th century.

The initial translation needs to be rough, but it gets us started. Sometimes I won’t even conjugate verbs and will just note something like – feeling generative 2nd person plural.

Depending on how your text will be used, the writing of footnotes or context notes can be really helpful. Here it does not make sense as the texts are for reading aloud.

On Biblical Grammar

There are no grammatical markings in the ancient Hebrew or Greek texts. I’ve included a sample from the Westminster Leningrad Codex, and the Codex Sinaiticus. This means we need to make interpretive decisions about the punctuation, sentences, and paragraphs.

Westminster Leningrad

Codex Sinaiticus

(source)

Revise for the Context

This is where those questions from earlier first come into play. There are often ways to render the same text in ways that are more simple, or more complex. In this case, we are choosing simplicity in vocabulary and structure. Beyond that, the texts are primarily going to be heard aloud. There is extra attention given to how they sound read aloud, chanted, and sung. This all starts to happen here.

Do it again and again

Keep going, and translating. As you do more in this segment, you may notice patterns or rhythms. If you do, try to find ways to let your words reflect this. One of the challenges is that Hebrew poetry has different patterns from modern English or French poetry. So we should try to bring in modern genre elements, lest we lose part of the experience of the original audience.

Revise the First Draft

When you get to the end of the passage, section, chapter, or book, you need to read it all. This process takes time, and we want to ensure the text itself sounds consistent. Now that there is more translated, we can do some intertextual work as well. Are the same ideas treated similarly? Did we render repetitive texts the same? Is the use of pronouns clear, or do some need to be replaced with their nouns? Are there sentences that just got away from us and need to be rewritten?

Contemporary Versions & Reference Work

We do not translate these texts in a vacuum. I have read the bible many times, in different languages, and in many translations. Those praying these psalms will be likewise diverse. We want to ensure that interpretive choices that were made are not going to be too jarring or dissident with the texts they may hear preached, or study in their bibles. This includes other prayer books like the Liturgy of the Hours, Book of Common Prayer, AELF, les Heures Grégoriennes, and others.

There is also the case of contemporary scholarship, and research. Are there things from other Ancient Near Eastern literature that might be informed/referenced by our text? Can that inform our rendering?

Closeness of English & French

This is unique to these translations in that we are attempting to keep the translations similar. The two languages have different grammatical structures, but I want to use this initial translation process to jumpstart both editions.

Usage of the Texts

After it has been translated, it needs to be used. In the process of using the text, you may discover issues with it. We should never expect a translation to be finished. We are imperfect people doing a very hard thing. Our cultures & languages change as well.

Most of the issues I have encountered in these Psalms have been around the flow of the texts, or a rendering that is too confusing. In the moment of the first draft with so much held in our imagination we can miss including something in the text. This can result in odd jumps, omissions, or clunky readings.

Peer Revisions & Review

No translation should be done alone. They are most often the work of a committee. I do not yet have that privilege. Our peer review will start after we make more progress, grow our community, and raise funds.

Concluding Thoughts

There are aspects of every translation process that are more art, and some that are more science. In light of this, these processes and approaches change and adapt with time. The scale and scope of this process may result in different approaches being used as we approach the end of the initial work. I have also not yet been a part of more revision & review processes.